Many of us want to progress to higher levels in our organisation as quickly as possible. A promotion – and a more senior position – gives us a sense of achievement and progress; it is also a visible validation of our fitness for bigger things. You can now do things that have an impact on the company as a whole. The money is better, and your social standing has improved. What’s not to like? After all, ambition and hunger for growth are basic human traits. Just keep pushing for more of the same, right? Not necessarily.

In our corporate life, we come across senior executives of many kinds. At one end of the spectrum, there are those who exude a sense of calm confidence and capability, and there are those at the other extreme who signal instability. The latter tend to make up for their insecurity with assertions of power and position. Their conversation is littered with references to “I” (and not “we” or “our company”). It is almost as if they are trying to convince themselves about their fitness for their role through these assertions. They also exhibit a remarkable lack of receptivity to feedback or advice because they believe they know it all.

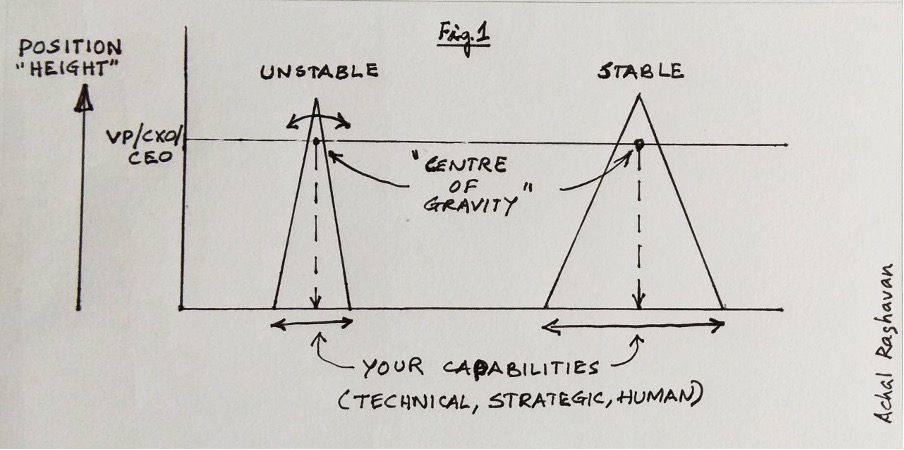

What is happening here? I see parallels with the concept of “centre of gravity” (COG) that we learnt in school. The higher the COG, the more unstable an object is, unless the base is sufficiently broad. In other words, an object with a high COG and a narrow base is likely to topple over at the slightest sideways push. You might recall seeing the diagram with a tilted object, where you draw a vertical line down from the COG. If this line falls outside the base, the object will fall.

Now, let us equate this centre of gravity with the “organisational height” at which a particular job is situated – say, BU Head, Vice President, CXO or CEO. When you reach that position, if your “base” – made up of your technical, strategic and human skills – is broad enough for that job, you feel secure, confident and calm. If, on the other hand, your base is too narrow for that organisational height, you are likely to feel wobbly and insecure with every passing organisational challenge (see Figure1). In other words, you are operating at a level that is too high for your current capabilities. This explains the unstable behaviour of some of the senior executives we come across in corporate life.

And so, as we aspire for greater heights in the organisation, we also need to broaden our capabilities continuously. The crosswinds that buffet senior executives in any company are getting stronger and more frequent. We, and the organisation, would be better off if we recognised this relationship between heights and stability and equipped ourselves with better and broader capabilities – technical, strategic and human – before making the next move upwards.

Regardless of how high your current position is in the organisation, continued learning is the key for maintaining your stability. Given the fast-changing environment, when you stop learning, you are actually shrinking your existing base because of its built-in obsolescence. You are thus creating future instability for yourself.

Understanding this dynamic phenomenon in real-time and acting on it requires a high degree of self-awareness and objectivity. That is hard to achieve. We are inherently biased about ourselves and tend to overestimate our capabilities. We need to counter this bias by developing a close relationship with another person who will be a good sounding board. It could be a friend, a classmate, a relative or a colleague – it does not matter. We all need someone who speaks the truth to us and keeps us grounded.