Global Evolution of Gender Diversity on Corporate Boards

The push for gender diversity on boards has a multifaceted history, evolving alongside broader societal shifts towards gender equality. Initially, the presence of women in corporate boardrooms was a rarity, reflecting the prevailing gender biases. However, as the 20th century progressed, notably from the 1970s onwards with the rise of the feminist movement, there was a growing recognition of the necessity for gender diversity in all spheres of public and corporate life. During This period, the number of women holding board positions increased gradually, although progress was slow and typically restricted to non-executive roles.

Gender Diversity: A Social Cause?

The dawn of the 21st century brought a pivotal change in discourse about board diversity. Scholars began to explore whether gender diversity was merely a societal objective or if it also yielded tangible benefits for companies. Initial studies revealed unexpected outcomes, showing that diversity in boards can lead to enhanced decision-making, better governance, and superior financial results. More recent research has identified several additional advantages of gender diversity on boards: (a) it promotes greater use of renewable energy, supporting the environmental sustainability of companies; (b) it decreases the cost of debt, favours shorter debt durations, and lowers financial leverage, thus reducing potential bankruptcy risks and impacts; (c) it drives innovation within firms; (d) it boosts the firms’ performance in corporate social responsibility; (e) it encourages higher distribution of dividends, diminishing the agency costs associated with equity and (f) it enhances the disclosure and assessment of bio-diversity impacts by companies.

As discussions about gender equality intensified and academic evidence supporting the benefits of gender diversity on corporate boards increased, various nations began to adopt policies and quotas to foster gender diversity. Norway, for instance, set a significant benchmark in 2003 when it passed a law mandating 40% female representation on boards, influencing Europe and other regions.

Over the last ten years, the narrative has shifted from considering gender diversity as merely a compliance issue to recognizing it as a strategic asset. Organizations like Catalyst and the 30% Club have been instrumental in promoting a minimum of 30% female board representation. Many countries have established either compulsory quotas or guidelines to encourage women’s participation in top-tier business decision-making roles. This change acknowledges that diverse boards better represent a company’s workforce and clientele, leading to more comprehensive and inclusive governance.

Regulatory Response to Gender Diversity on Corporate Boards: India

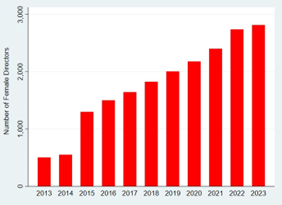

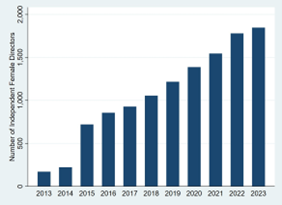

Mirroring the initiatives observed in several European nations, India too has implemented a quota system, albeit on a considerably lesser scale, to boost the presence of female directors in boardrooms. The landmark Companies Act of 2013 was a significant turning point, requiring a specified category of companies to appoint at least one woman director. This legislative effort marked the beginning of a gradual yet discernible shift, leading to an uptick in the representation of women in corporate board roles. Based on our research using the India Boards Data from Prime Infobase, we find that in the nine years since its inception, the number of women on boards has increased by nearly five times. There is evidence of a similar trend for female independent directors (see figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Number of Female Directors in Indian Companies (2013-2023)

Figure 2: Number of Independent Female Directors in Indian Companies (2013-2023)

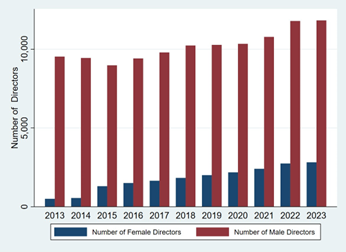

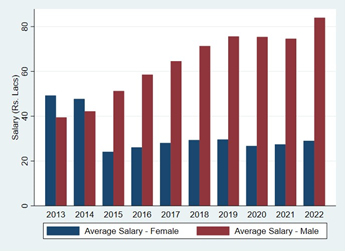

Consequently, the regulation has been moderately effective in shattering the glass ceiling. Yet, a comparison of the number of female to male directors, shows that the board positions in India continue to be dominated by men (refer to figure 3). Furthermore, before it became compulsory to appoint women to boards, female directors were generally paid more than their male counterparts.

Figure 3: Number of Female Directors vs. Male Directors in Indian Companies (2013 – 2023)

Figure 4 illustrates that before the law mandating female director presence on boards was passed, women directors earned more than their male counterparts. However, following its enactment, their renumeration reduced to less than one-third of what it was. This suggests a concerning trend when we consider directors’ pay as a reflection of their expected contribution to assessing and enhancing company performance. The significant reduction in average pay of female director hints that firms might not view the newly appointed female directors as major contributors. A plausible explanation for this disparity, especially after the legal mandate for female representation on boards, could be the appointment of “token directors.” as they are referred to in academic circles These are directors who are chosen more for symbolic reasons and to comply with regulations rather than for their potential impact. Such “token directors” are often perceived as having limited influence within their boards, making them less likely to drive substantial change.

Figure 4: Average Salary of Female vs. Male Directors in Indian Companies (2013-2023)

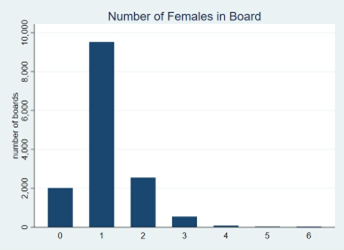

To determine if the appointment of “token directors” for compliance purposes was prevalent in India, we explored how the concept of tokenism is defined in academic research. There is growing consensus that a board consisting of only one or two female members does not fully capitalize on the advantages of gender diversity. The argument is that a certain minimum number of women is needed for their opinions to be effectively heard in predominantly male boards. Although there is no agreement among scholars on the exact number that constitutes this “critical mass,” it is generally accepted that having only one (or even two) female directors typically signifies tokenism. Figure 5 shows that the legislation has not achieved a significant female representation on most corporate boards. This observation reinforces the notion that while many Indian companies have met the legal requirement by appointing at least one female director, India still has a considerable way to go to truly reap the benefits of female participation in boardrooms.

Figure 5: Number of Boards with Number of Females during the 11-year Period from 2013 to 2023

The Way Forward:

To devise impactful changes, we must first grasp why the presence of female directors in firms improves corporate performance. According to a recent Harvard Business Review article based on interviews with various board members, the enhanced performance of female directors is largely attributable to skill and idea diversity. Essentially, the real value stems not solely from the director’s gender, but from their unique skill sets and diverse ideas influenced by different work experiences. Boards that seek a range of skills and experiences tend to boost firm performance.

With this insight, we propose two solutions for enhancing gender diversity on corporate boards while maintaining director effectiveness. The first is for regulatory authorities to enforce a rule ensuring minimal pay disparity between male and female directors. Given the equitable compensation, this approach could motivate companies to value skill and competence in their female director appointments.

The second solution entails taking action at the level of fund managers or Asset Management Companies (AMCs). Similar to ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) funds, we need investment funds that are specifically focused on board diversity. These funds should also educate investors about the advantages of a diverse board. As investment in such funds grows, both in terms of investor numbers and assets under management, it is likely to positively influence the stock prices of companies they invest in. If these funds carefully select companies that demonstrate genuine gender and skill diversity on boards, rather than mere tokenism, companies will be incentivised to go beyond merely complying with legal requirements. The increase in ESG funds has already improved the ESG performance of many firms. It is high time we achieved the same success in ensuring board gender diversity.

Authors:

Amish Dugar, Shobhit Aggarwal & Sandhya Bhatia